Australian Mining Companies Digging A Deadly Footprint in Africa

Jul 10, 2015 • Will Fitzgibbon, Martha M. Hamilton and Cécile Schilis-Gallego

In the late afternoon of Friday, Oct. 15, 2004, Col. Ilunga Ademar, a 64-year-old father of 20 nicknamed the “double-bladed knife” and known for violent outbursts, led a brigade of government troops of DRC’s 62nd Infantry Division into the town of Kilwa in southeastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

The previous morning, the lakeside home to several thousand farmers, fishermen and their families had been taken — with a few shots in the air and without a drop of blood — by a handful of rebels led by a 20-year-old in sandals, trousers and a striped polo shirt.

The rebels had come to liberate the town, they announced, claiming Russia was on their side. But, fearing government response more than the young rebels, nearly all of Kilwa’s residents fled.

Witnesses remember hearing rumours of Ademar’s orders: “Kill everything that breathes.”

Forty-eight hours later, the rebels had been routed, and 73 men, women and boys were dead. Twenty-nine men had been summarily shot, slumping into a roadside pit turned mass grave. A family of seven, including a two-month old boy, drowned when the boat spiriting them away was upturned by mortar fire. The daughter of the town’s police chief, Pierre Musopelo Kunda, lay injured by a gang rape as her father, accused of treason, was tortured in a nearby hotel. She died months later from her injuries.

Townsman Christophe Musinge Samba was among those trucked to the pit on Kilwa’s outskirts at dusk for execution. “I was very scared,” remembers Samba, now an elderly man with sunken eyes who still regularly criss-crosses Kilwa’s unpaved roads on his bicycle.

“Scared, as you can imagine, because no one likes to die.”

Samba survived when the body of a fellow villager, shot in the head, knocked him down. Unseen by the soldiers, says Samba, he waited hours under cooling corpses before fleeing into the forest.

The road from Dikulushi mine passes through Kilwa on the way to the port on Lake Mweru. Photo: Eleanor Bell

The trucks, leased planes, jeeps and rations that soldiers used in this attack were provided to the infantry by Anvil Mining, then a copper and silver producer traded on stock exchanges in Canada and Australia whose isolated Dikulushi mine lay 50 kilometers (30 miles) from Kilwa. One United Nations investigator remembers seeing blood in the beds of two trucks parked at Anvil’s offices in Kilwa when she visited days later.

Although the mine was never directly threatened, Anvil suspended operations for five days and evacuated staff.

Dikulushi mine lay at one end of the road that passes through Kilwa to the port on Lake Mweru from which the mine’s copper and silver was shipped. For every day the mine was closed, the company lost up to an estimated $380,000 in sales.

Anvil, which sold the Dikulushi mine in 2010 and was itself purchased by Melbourne-headquartered Minmetals Resources Limited in 2012, confirmed that it provided equipment but rejected allegations that it assisted in, or knew of, human rights violations.

Following significant media attention, Anvil released a statement on June 7, 2005 that said: “the DRC military requested access to Anvil’s air services and vehicles, to facilitate troop movements in response to the rebel activity. Anvil had no option but to agree to the request”.

The only written evidence of any official order by DRC authorities for Anvil to assist the military is dated June 11, 2005 - eight months after the events at Kilwa and following public pressure and media attention. Critics point to the fact that no company representative mentioned the order in the months immediately after the massacre. Congolese lawyers reject its validity, and critics have suggested the company was “retrofitting” the facts to suit its case, noting that the company wasn’t compensated for the use of the equipment.

Executive director of British NGO RAID Tricia Feeney.

“This was a company-facilitated massacre,” says Tricia Feeney, executive director of the British non-governmental organization Rights and Accountability in Development. Feeney has followed the Kilwa case for a decade on behalf of its victims, who are seeking, a civil trial this year in Australia.

Previous attempts at class actions in Australia and Canada have fallen at procedural and jurisdictional hurdles, including alleged death threats in the DRC that prevented lawyers from speaking with victims.

Without Anvil’s transport and assistance, said Feeney, during a break in meetings on a visit to Washington D.C., “the soldiers could not have come to Kilwa and perpetrated one of the most serious massacres in recent times involving a mining company…..anywhere in the world, including Congo.” Feeney calls Anvil’s decision to supply equipment to Ademar “criminally naïve” given the colonel’s reputation for brutality.

“There have been multiple government enquires in a number of countries,” former Anvil CEO Bill Turner told ICIJ, “including a detailed Australian Federal Police investigation in Australia into those allegations. None of those enquiries has found that there is any substance whatsoever to the allegations. In addition, there has been litigation instigated in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Western Australia and Canada, which has at least touched on the matters raised by you. In none of those cases have there been findings against Anvil.”

Anvil Mining claims it was ordered by DRC authorities to assist the military. Photo: Eleanor Bell

Australian companies’ footprint

Anvil Mining was a pioneer, leading the West’s re-entry into a country reeling from a coup d’état, a three-year civil war and a presidential assassination. The company had come to the DRC in 1995 with high hopes. “Cashed up with a million dollars in the bank, we set off to Africa to see what we could do,” recalled Turner during a 2011 industry luncheon.

A report prepared for the company noted that “the neutral profile of an Australian company” pleased DRC leaders. It soon had powerful political friends, including one of the president’s close advisors who sat on the board of directors.

While the Kilwa massacre is unique in its severity, it is part of a pattern of Australian mining companies whose activities have been implicated in death, disfigurement, environmental destruction and displacement across Africa, according to ICIJ’s Fatal Extraction investigation.

That mining in Africa provokes controversy, even violence, is not new. Chinese companies receive regular criticism. Canada, too, has been forced to confront allegations of violence and even slavery linked to its mining companies. The Canadian parliament has gone as far as debating a bill that would have tightened government oversight of resource companies in developing countries. It failed, narrowly.

We looked at Australia’s dramatically increasing role in exploring and developing mining projects on the African continent because it has been less examined.

What ICIJ uncovered and pieced together suggests a troubling track record by Australian companies in the rush for Africa’s minerals, including practices that would be impermissible and unthinkable within Australia and other parts of the developed world.

ICIJ analysis found more than 150 Australian-listed active mining companies listing properties in Africa at the end of 2014. Other estimates with different criteria put the number higher.

While other countries have poured more money into African mining during the past ten years, the pure number of Australian companies has outstripped its rivals. In Botswana alone, for example, Australian companies went from holding 14 prospecting licenses in 2000 to 260 in 2009. Even as the mineral market cools, Australian companies continue to seek mining rights from Togo to Madagascar.

Many of these companies appear to have clean records and are well received. They include well-known companies and also small explorers worth less than $1 million that snap up licenses in the hope of striking it rich. Together, they control land in deserts, national parks and mountains across tens of thousands of square kilometres over 33 countries.

It is a vast — and in some cases deadly — footprint.

ICIJ’s investigation, combining Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) data analysis and on-the-ground reporting, reveals the scale and impact of Australia’s mining presence in Africa as it has grown over the last decade.

For months, ICIJ and journalists from more than 10 countries pored over thousands of documents to compile information often deeply buried inside annual and quarterly reports, license registries, ASX announcements and company presentations. Journalists submitted freedom of information requests, searched archives and conducted interviews in a dozen languages. From Niger to Tanzania, journalists scoured regional courthouses and gained the confidence of communities, employees, prosecutors and defense lawyers to unearth legal filings, hand-written petitions and incident reports gathering dust in broken filing cabinets across Africa.

It is one of the largest-ever journalism collaborations in Africa and brings together reporters from South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia, Mali, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Senegal.

According to obtainable records, more than 380 people died in on-site accidents or off-site skirmishes linked to ASX-listed mining companies since the beginning of 2004. For the same period in Australia’s mining sector, the federal agency Safe Work Australia lists 107 workplace deaths.

Military interventions linked to mining activities have sometimes erupted into violence. Photo: Eleanor Bell

The number across 13 countries in Africa includes workplace deaths officially reported to the ASX. But mining’s impacts can be more widely felt than just in industrial accidents, and ICIJ has included people killed away from mine sites in incidents, protests and military interventions linked to which these companies, even in cases where companies deny liability.

“Mining is a risky and dangerous business, but in Australia we have the protection of trade unions and robust laws to prevent the risk of fatalities, violence and conflict,” says Serena Lilywhite, mining advocacy coordinator at Oxfam Australia. “This is not that case in many African countries.”

Exact comparisons are difficult, and factors such as the type of mineral produced and the level of mechanization in different countries influence fatality numbers. But, counting workplace fatalities alone, South Africa’s mining industry has a fatality rate four times higher than Australia’s.

Thousands of people, including village chiefs and tribal headwomen, elected representatives, former employees, traditional healers, human rights defenders and government agencies have taken Australian companies, their subsidiaries and their contractors to court across Africa for alleged negligence, unfair dismissal and eviction, illegal licensing or pollution, according to court submissions and judgments unearthed from more than a dozen countries.

Home and away

In many ways, the two mineral-rich continents are odd bedfellows, with little in common beyond some business and mining ties and a passion for cricket and rugby.

The mining industry has treated the continents very differently.

Starting salaries for Australian mine workers sit around $60,000, while the median minimum mining wage in South Africa, the best paid jurisdiction on the continent, touches $5,500. In contrast to mining operations in Africa, where wages are often the only reliable compensation, Australian workers commonly count on paid sick, annual and family leave, holiday rates and pensions.

Australia’s mining industry, while not fatality-free, leads the world in safety standards and compensation when accidents do occur. But these standards are not always applied by companies and government agencies in Africa, employees and critics say.

In Australia, victims of workplace accidents in some states can expect a lump sum payment of more than half a million dollars. In contrast, the International Labor Organization (ILO) reports that when it comes to workplace compensation in parts of Africa, “compliance is low, record keeping is poor, and delays in payments are frequent.” Across southern Africa, injured miners with missing limbs or in wheelchairs — often illiterate, impecunious or confused by bureaucracy — can go years without receiving compensation due under law. Or never receive it at all.

When mining tragedies do strike in Australia, detailed coroners’ inquiries and warden reports are common. After the 1994 disaster at Moura Mine in Queensland, experts and lawyers met for three months, hearing from 66 witnesses, analysing 300 exhibits and collecting 5,000 pages of transcripts. In Beaconsfield, Tasmania, where one miner died in 2006, a year-long inquiry sifted through 100 interviews and 4,000 company emails.

The cost of Australia’s high standards, however, sometimes rankles industry executives.

Environmental and social protections at home are “overly sophisticated” and indigenous land claims make the country “difficult,” mining executives grouse.

Africa, on the contrary, offers “low costs of production,” said John Welborn, managing director of Equatorial Resources, in 2012 remarks to the Sydney Mining Club. Once production begins at its iron ore mine in the Republic of Congo, the company will pay less than half the royalty rate it would at home, no tax for five years and never more than 15 percent, under an agreement including “favourable fiscal terms” signed with the Congolese government, one of many African governments to offer tax incentives and other financial enticements.

Mirroring corporate enthusiasm, consecutive Australian governments have cheered Australia’s entry into Africa’s mining market that boomed over the last ten years. Of the companies recently active in Africa, nearly 60 percent have listed since 2004.

“What I am going to do with that?”

South of Kilwa, in the strip-thin nation of Malawi, another Australian mining pioneer has faced accusations from communities and former mine workers for years.

The fingers on Caldwell Sichinga’s right hand were fused into a mitt by an explosion at a mining site. Photo: Will Fitzgibbon

In 2009, Caldwell Sichinga, then in his early thirties, was cleaning the bottom of a seven-meter steel tank at Kayelekera, a remote open-pit uranium mine in Northern Malawi. It had rained during the night and Sichinga was reapplying a coat of MEK, a combustible chemical that smells slightly of mint.

Sichinga was with two colleagues inside when the tank suddenly blew. In order to ignite, an expert told ICIJ, the concentration of MEK must have been at least 70 times the level considered safe within the U.S.

“It was like a bomb,” remembers Sichinga.

Through the fireball, Sichinga climbed his way up the rungs inside the tank, searing the soles of his feet with every step, before falling to the ground outside. The explosion fused the fingers of Sichinga’s right hand into one immobile mitt and appears to have melted the pattern of his socks into his ankle.

Four meters from the tank, others had been “busy grinding and welding,” according to the preliminary incident report issued by the principal contractors and obtained by ICIJ. As the MEK evaporated, its heavy fumes coursed through the tank’s drainpipe to the welding outside. The fumes ignited when they reached the heat source, according to the report, sending flames back through the drainpipe towards the three contractors.

“Based on information in the initial company incident report, clearly MEK’s high flammability (a flash point of only -6.6 degrees C) would require work causing sparks (grinding) and flames (welding) should have been located at a much greater, safer distance than the incident report’s 4m,” wrote Mike Roop, an expert who appeared in litigation involving one of the U.S.’s biggest-ever mine explosions and who was asked by the ICIJ to examine the preliminary incident report.

Paladin told ICIJ “the cause of the flash fire remains in dispute” and that no opinion could be based on “full possession of the facts.” The company declined, however, to release supplementary reports on the causes of the explosion, citing ongoing legal proceedings.

An accident report written by a local Malawian official after the accident and seen by ICIJ confirms that something went wrong. “MEK is not usually used on the site,” the project’s safety manager told the Malawian official, so the contractors’ “failure to communicate … could have been one of the causes of the accident.”

Over the next two days, the “fire accident” prompted 200 contract workers to strike over pay and working conditions, reported the same official in another document seen by ICIJ.

Sichinga blames the fire on another worker reportedly seen smoking near the tank. The worker didn’t hear shouts of warning, Sichinga believes, and flicked the butt to the ground.

The Australian flag flies over an entrance to Paladin’s Kayelekera mine in Malawi. Photo: Eleanor Bell

Paladin Energy, the Australian company whose subsidiary, Paladin Africa, was engaged in the construction phases of its future uranium mine, reported the March 16 explosion to the ASX. With injuries so severe that Malawi’s own doctors couldn’t cope, Sichinga and his colleagues were sent for treatment in South Africa. One colleague died within days. The second endured another two weeks.

Paladin Africa told ICIJ that victims were employed by contractors and that the company “ensured that a first-class health and safety system was in place and enforced on the site.” Prior to the incident, Paladin wrote, the project had an exemplary safety record.

“Paladin denies any negligence on its part and maintains that the Company acted humanely and with the utmost compassion in trying to afford the three injured contractors their best chance of survival in circumstances where none of the parties directly responsible for their welfare did so. It is undeniable that Mr. Sichinga would have succumbed to his injuries if Paladin had not acted as it did on his behalf.”

Paladin told ICIJ it spent $1 million “on air evacuation, medical and rehabilitation costs — mostly relating to Mr. Sichinga’s treatment.” In addition, the company told ICIJ, “it decided to provide further ex gratia assistance to assist Mr. Sichinga to lead as normal and comfortable a life as possible on his return to Malawi.” This includes nearly $10,000.to renovate Mr. Sichinga’s house with new brickwork and windows, a latrine, shower and storeroom block, a solar panel, battery and fan.

“In addition to upgrading his residence, the Company has provided Mr. Sichinga with a monthly stipend of up to $150 as well as meeting the cost of his medications.

“Paladin’s view, based on legal advice it has received, is that the other parties are liable for Mr. Sichinga’s damages,” wrote the company.

As a result, Paladin has not offered Sichinga compensation. Sichinga’s direct employer, a contractor on-site during construction of Paladin’s mine, reportedly offered Sichinga the minimum legal requirement of 42 months’ salary.

Sichinga is still receiving treatment following the 2009 explosion. Photo: Eleanor Bell

It’s an offer Sichinga, whose civil complaint against Paladin and one contractor is ongoing, refused.

“950,000[Malawian Kwacha or $2,200]? What I am going to do with that?” asks Sichinga, a father of five. “If I was a white man, would you give me such a type of amount?”

Paladin told ICIJ: “Mr. Sichinga has not accepted the payout despite advice that doing so will not prejudice a civil claim. Given Mr. Sichinga’s misunderstanding in this regard, it is likely that his comment concerning treatment of a European employee is a similar misconception… The fact that Paladin evacuated Mr. Sichinga and his co-workers to Millpark Hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa, regarded as one of the finest medical facilities in Africa for the treatment of burns cases, is evidence that Paladin made no distinction based on race.”

When a basic wage earner in Australia is permanently injured or disabled on the job, the worker can choose to receive either 75 percent of earnings for the rest of the employee’s estimated working life or lump-sum compensation of $414,000.

Three more workers at the same mine, including a contractor, have died in other incidents at Kayelekera in the years after the fireball. There has been no finding of wrongdoing for these deaths.

Paladin has faced other criticisms inside Malawi. Before Paladin dug the first hole, Malawian civil society organizations challenged its mining license in the country’s High Court, alleging the company and the government risked the health of those living nearby. While the parties settled in 2007 out of court, in April an NGO applied for an interlocutory injunction to prevent Paladin from disposing uranium waste in neighboring rivers.

In the regional Ministry of Labour office close to Paladin’s operations, a faded, hand-written ledger records more than 40 entries between 2010 and 2013 from employees with grievances against Paladin Africa and its subcontractors relating to alleged unfair dismissal, underpayment or nonpayment of salaries or retirement benefits. Most were marked as resolved either through payment or court referral. A manila folder nearby, marked “Paladin,” contains meeting minutes, records of contractor employee strikes and sit-ins and a request from the Ministry to borrow Paladin’s car tires.

The company does not have a troubled industrial relations history, Paladin told ICIJ, noting that “not a single complaint or action against the Company has been upheld.”

A platinum mine in northern South Africa seen from a nearby informal settlement. Photo: Eleanor Bell

Contractors: cost-cutting with a risk

Malawi isn’t the only place where contract workers lost their lives.

Early one evening in July 2010, a thick slab of rock the size of a cricket pitch fell from the ceiling of the Marikana underground mine, operated in South Africa by Aquarius Platinum, an Australian-listed company. The rock killed five contract workers drilling 70 meters (u.s. measure) underground. When rescuers finally brought the miners to the surface, their faces were crushed beyond recognition and the men could be identified only by fingerprints and numbers on their cap lamps, a witness remembers.

Contractors were a key feature of Aquarius’ operations despite studies that show that their use in the mining sector increases deaths and injuries.

In 2002, Aquarius Platinum entered South Africa promising potential investors “Australian ideas in an Africa context,” highlighting contract mining as part of the “Aquarius way,” according to the company’s presentation. Australian mine workers are more likely to work directly for the company than mine employees in Africa, who are regularly hired as contractors.

True to its word, by 2011 Aquarius Platinum employed more than 80 percent contract labor, more than any other major platinum producer in South Africa. It became the world’s fourth-largest producer of platinum, the precious gray metal used in diamond necklaces and car parts.

Aquarius’s operations were profitable, but it also reported the second highest number of on-site fatalities among active Australian-listed mining companies — 38 between 2004 and 2014. That’s more than all deaths during the same period in Western Australia, which has at least five times as many employees as Aquarius.

South Africa, the continent’s mining powerhouse, has reduced the number of mining deaths over recent years. But its fatality rate is still more than four times higher than Australia’s.

A South African miner wears a t-shirt marking a recent death at Aquarius Platinum’s Kroondal mine. Photo: Eleanor Bell

“That sort of toll, I can only say, would not be tolerated here,” professor Michael Quinlan, director of the Industrial Relations Research Centre at the University of New South Wales and author of multiple official inquiries into fatal mine accidents, told ICIJ in an interview.

“In Australia, if a company has had a run of fatalities, it wouldn’t need to get anywhere near 40 before the mine inspectorate would start to get very concerned,” said Quinlan.

“In some situations, there may be very good reasons to use contractors,” says Quinlan, but “contractors won’t always report issues because they’re afraid they’ll lose their work.”

Using contract workers saves money, says Quinlan, but “it creates an enormously more difficult safety regime to manage.”

Following the 2010 rock fall, South African authorities sent in safety inspectors and temporarily shut the mine.

Erick Gcilitshana, health and safety secretary at South Africa’s National Union of Mineworkers, went underground after the accident as part of an initial investigation team. He remembers seeing what he said were three violations of the company’s code of conduct, including roof bolts twisted dangerously at ninety-degree angles.

Asked about that, Aquarius told ICIJ it was unable to comment regarding particulars.

“Aquarius has acknowledged that the terrible accident at Marikana’s 4 shaft in July 2010 was the worst in the company’s history as a platinum miner,” the company told ICIJ. The victims’ families are legally entitled to financial compensation, and a formal day of mourning was held.

“Following this accident,” the company said, “Aquarius redoubled efforts and commitments to safety and agreed and implemented new and additional hanging wall support and fall-of-ground safety measures at its South African mines.” The company’s board concluded that South Africa’s countrywide standards were “not acceptable” and Aquarius began “championing updates and revisions” of the country’s mining standards.

Since the rock fall, Aquarius has reported the deaths of nine more contractors and Aquarius employees. There have been no findings of wrongdoing in these cases.

Aquarius is “more than compliant” with South Africa’s mine safety laws, the company told ICIJ, including comprehensive codes of practice, standards and procedures. An industrial dance group and “drumming sessions” are among tools used to communicate safety information.

The company changed its contractor employment model in 2012, explaining the decision as “essentially the result of a cost/benefit and alignment analysis.”

“Today, our use of contractors is in line with South African industry norms.”

The uncounted

Australian companies tell the ASX when a worker dies at a mine the company owns or operates. Any major event or accident, from a strike to a sludge spill, is also reported if a “reasonable person” may think that the company’s value could be affected by costly investigations, production freezes or compensation pay-outs, according to ASX rules.

Away from the workplace and off-site, the rule doesn’t always apply. Injuries, accidents and deaths linked to or provoked by Australian mining activity — but away from the mine itself — are not always reported. If a local government takes no action, for example, or if a victim can’t afford a lawyer, incidents might simply be forgotten.

Resolute Mining Limited, a Perth-based company, never reported a deadly protest in the Malian commune Fourou, an impoverished huddle of villages surrounding its Syama gold mine.

Under ASX rules, it didn’t have to. But while the event doesn’t appear in the company’s history, it has marked a community forever.

Before dawn on 9 November 2012, local men began piling tree branches on the road to the the Syama mine. The blockade would not be removed until three villagers, arrested days earlier for allegedly assaulting a mine subcontractor’s human resources manager, were released, protestors said. Locals had complained for years about alleged discriminatory employment practices. Although Syama’s gold wealth has been exported by various companies since 1990, the area is one of the poorest in Mali and sub-Saharan Africa. It was the third time villagers had blocked the road.

“Our goal wasn’t warfare,” said Moussa Kone, a father or nine and one of the first to join the protest. “If that was our goal, we wouldn’t have taken our family.”

The men refused to leave and spent two nights sleeping outdoors. Women who came to deliver breakfast stayed on to protest, waving ladles and kitchen utensils. By Sunday, at least 100 protestors had joined the barricade.

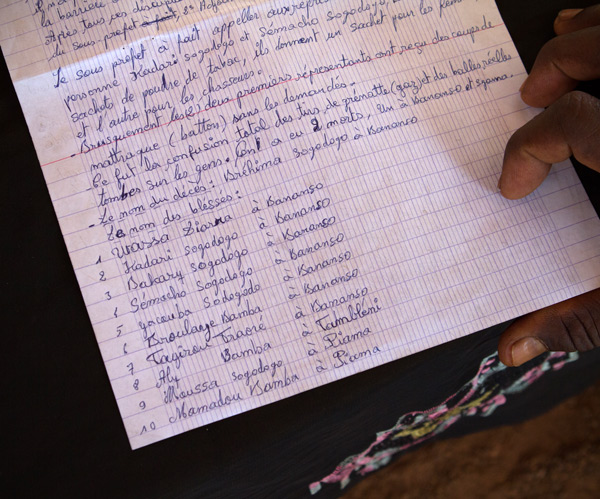

A list of people allegedly injured by police in a protest in Mali. Photo: Eleanor Bell

The sun rose, and heat intensified. Negotiations had failed. Police and gendarmes in riot gear were in position. The local prefect authorized the use of firearms, according to an official document obtained by ICIJ.

Sidiki Diarra, a local police officer, confirmed to ICIJ that the mine called and asked authorities to unblock the road.

“The armed people came towards us like they were going to war,” remembers Kone. “They were yelling, making noise.”

A bullet ripped through one protestor’s throat, he told ICIJ. Others, including a 70-year-old woman, sustained bullet wounds in their legs and feet.

“I’m hit,” Semacho Sogodogo remembers hearing during the shooting. It was his friend, Brehima Sogodogo (no relation). As the crowd fled, Semacho, 37, loaded Brehima onto his motorbike and raced home over the red, dusty earth to their village of Bananso.

“Brehima was still breathing right up until we entered the village,” remembers Semacho. That’s when Semacho heard a loud sigh he knew to be his friend’s last. Brehima was dead by the time the motorbike pulled into the village, according to Semacho and a village nurse who saw the corpse, punctured by one bullet hole through the abdomen.

“We are not a village of warriors,” says Semacho. “We welcome everyone. But what we don’t like is to be dragged through the mud and disrespected.”

Too poor to pay lawyers, villagers have never received compensation. Perceived employment discrimination still riles, according to minutes obtained by ICIJ of meetings between company representatives and locals.

“We are in favour of a win-win partnership,” says El Hadj Issa Sissiko, regional president of the Malian Association for Human Rights. “But when the subsoil disgorges gold, it is difficult to accept that the population remains destitute from year to year.”

Peter Sullivan, CEO of Resolute, told ICIJ via email that “there have been some instances where some people in the local community feel aggrieved by our presence or operations, for a variety [of] reasons. This is not unexpected given the large role the mine plays in the region. Resolute is committed to addressing those concerns where it can and discussing the issues where a pathway forward is not readily apparent.”

Resolute had established a community committee that oversees local employment, said Sullivan, “with the result, that for example, nearly 80% of all unskilled labour is sourced from local communities.”

Sullivan declined to answer specific questions about the protest.

Although not legally required, many believe that Resolute Mining should have told investors about the bodies, bullet casings and burials of November 2012. The uncertainty in such cases, experts say, is a symptom of Australia’s unwillingness to lead the global movement to require companies to disclose social and environmental risks, including those incurred abroad.

It has been this way for years.

In June 2005, Australia’s Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services launched an inquiry into corporate transparency, including what corporations should make public to their shareholders and the broader community and whether new rules were needed. It followed concern that investors, the public and regulators weren’t always getting the full story.

“We are not quite sure why we do not compare well internationally,” confessed an official during a hearing in response to questions about non-financial reporting by ASX-listed companies as a whole.

“We’re basically saying, ‘We trust you to report on what you think is right’ … And we have enough proof that that doesn’t work.”

The committee heard opposing arguments. Corporations and their lobbyists, the joint committee’s report said, “almost unanimously agreed” that the status quo was acceptable. Academics, NGOs and accountants, on the other hand, saw “scope for improvement.”

The inquiry ultimately sided with the companies, keeping reporting voluntary so that, for example, a small fine for violating local laws need not be reported.

Since then, Australian companies have improved, and large mining companies are often cited as leaders. But Australian companies overall still report less than those from countries such as the U.S., Canada and South Africa.

“In Australia, we’re basically saying, ‘We trust you to report on what you think is right,’” says Justine Nolan, an associate professor of law at the University of New South Wales. “And we have enough proof that that doesn’t work.” Nolan was among those who recommended that Parliament adopt mandatory reporting and clear guidance on when companies should disclose social and environmental issues.

“What happens is that everything keeps getting swept under the rug,” says Nolan, “and you have the opportunity for companies to just say, ‘That’s not our business. Yes, this is our mine and it would never have happened but for the mine being there, but, still, we’re not responsible.’”

Last chance

Three years after the Kilwa massacre, Colonel Ademar, a handful of soldiers and three Anvil managers faced a Congolese military tribunal. From behind white table cloths on a raised stage, judges addressed the accused below who sat on blue plastic chairs.

The trial didn’t go smoothly; the prosecutor was re-assigned mid-case, a legal advisor to victims joined the defense team, and lawyers weren’t always present at hearings. After six months, the court cleared all defendants, including Anvil’s men and the company itself, even though it was not charged. Judges wrote there was no evidence of human rights abuses.

Ademar, who has since died, was convicted during the same trial of murdering two men in an incident unrelated to Kilwa.

Not a single relative of those killed has received compensation.

Photo: Eleanor Bell

Many still feel that important questions remain unanswered about Anvil’s role and what it has said in its defense.

“Anvil did not receive a legal order capable of excluding its liability,” Marcel Yabili, a Congolese author and lawyer with 45 years’ experience, told ICIJ in an email, referring to the official document dated eight months after the massacre that says Anvil provided equipment under government orders.

“First, the order should have been provided in writing and before the logistics were provided in 2004 but not several months later in 2005,” Yabili said. Second, he added, the company never exercised its right to be reimbursed for government use of company equipment.

“Anvil never raised the issue of a bill to be repaid,” explained Yabili. “It did everything for free. There was a voluntary participation in the military action, and therefore the company shares responsibility in the wrongs and the damage.”

The Human Rights Law Centre in Melbourne has been speaking to Kilwa families about bringing a last-ditch civil class action in Australia. Any Australian legal action would face challenges, lawyers say, and would be the first real test of corporate Australia’s record in Africa.

“What we just aim at right now is that the justice system in the country of origin of … Anvil Mining would hear us,” says Dickay Kunda, surveying his neighbour’s brood of chickens in the suburbs of Lubumbashi, DRC’s mining capital. Kunda’s father was tortured and his sister was raped during the massacre.

“We need to be heard in Australia,” says Dickay Kunda. “That’s our last chance.”

This story was supported by funding from Australian philanthropist and businessman Graeme Wood, and the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Contributors to this story: Friedrich Lindenberg

actNOW!

Register for updates and alerts on ANCIR Investigations.